Narco State

A Double Assassination

I was drinking a coffee at Baiana when the Afropop music played by the local radio suddenly stopped. A frantic speaker was trying to report about a blast that had just killed a few soldiers, destroying the military headquarters.

I jumped in my car and drove toward the military compound. When I arrived everyone was shouting and running through the smoky ruins of the building. Bissau’s only ambulance was coming and going from the hospital to pick up the bodies of the victims. Four heavily armed soldiers pointing their AK-47 at my face discouraged me from taking photographs or asking questions. All they told me was that General Batista Tagme Na Wai, head of the army, had just been assassinated. I went back to the car and headed to the hospital.

On that night, Bissau’s sleepy routine was broken. I made some phone calls to find out what was going on, even as the Minister of Defense arrived at the hospital and ordered the police to keep journalists away. After two hours trying to get information I left the hospital, heading to my hotel. At the reception everyone was trading theories. Someone said it was a coup d’etat, others that it was an accident, a bomb, or the beginning of another civil war. I went to my room and tried to sleep.

Originally Published

Author

Marco Vernaschi

Media

Time, New York Times, Newsweek, Sunday Times, Internazionale, VQR, Global Post, El Pais, BBC, FRIJ, Suddeutsche Zeitung, L'Espresso, Frontline Iwitness CBC

At six in the morning my friend and informant Vladimir, a reliable security man who works at the hotel, knocked on my door. He was frightened, and told me that the president had just been killed. When I asked him how he knew, he simply shook his head. I instantly left my room and went to the President’s house. Soldiers there were shooting in the air, to keep a little crowd of people away from the house.

A bunch of soldiers with machine guns and bazookas surrounded the block. The president’s armored Hummer was still parked in front of the house, the tires flat and its bulletproof windows shattered. The police cars from his escort were destroyed. A rocket shot from a bazooka had penetrated four walls, ending up in the president’s living room. Joao Bernardo Vieira was dead, after ruling Guinea Bissau for nearly a quarter of a century.

After a few hours waiting in front of the house I understand I wouldn’t have been allowed any access this day. A soldier came toward me and seized my camera to check if I had taken any pictures. Fortunately I had not, and he gave me the camera back. It was time to leave.

In just nine hours Guinea Bissau had lost both it president and the head of its army. Why so much violence? Was this double assassination the result of an old rivalry between Vieira and Tagme, or was it something more? The army’s spokesman, Zamora Induta, declared that the president had been killed by a group of renegade soldiers and that assailants using a bomb had assassinated General Tagme. He said there is no connection between the two deaths. Of course, nobody believed that this was so.

In the last few years Guinea Bissau had become a major hub for cocaine trafficking. The drug is shipped from Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil to West Africa en route to its final destination in Europe. Were these assassinations linked to drug trafficking?

After paying a useless visit to the president’s house, I headed back to the military headquarters, where the situation was still tense but the press was finally allowed in. I took some pictures of the destroyed building and sneaked out from the generals’ view, reaching a backyard where some soldiers were resting, sipping tea under a big tree. I joined them, trying to be friendly. I offered cigarettes and had tea in return, so we started to talk about what happened to General Tagme Na Wai and to President Vieira, when Paul — the chief of a special commando unit from the region of Mansoa — told me they had had a hell of night. He wore a denim cowboy hat and two cartridge belts across his body, in perfect Rambo style.

At first I thought he was referring to the general situation, but then he proudly told me that he and his men were sent to the president’s house, to kill him. It was noon, the sun higher than ever. My blood froze. My first reaction was actually not to react. I simply answered with a skeptical “really”, and let him talk.

“The President is responsible for his own death,” said Paul, in French.

“We went to the house, to question Nino (as the president was called) about the bomb that killed Tagme Na Wai. When we arrived he was trying to flee, with his wife, so we forced them to stay. When we asked if he issued the order to kill Tagme, he first denied his responsibility but then confessed. He said he bought the bomb during his last trip to France and ordered that it be placed under the staircase, by Tagme’s office. He didn’t want to give the names of those who brought the bomb here, or the name of the person who placed it.“

At this point, the quality of the details started to convince me that Paul wasn’t lying.

“You know, Nino was a brave man but this time he really did something wrong. So we had to kill him. After all, he killed Tagme and made our life impossible… we are not receiving our salary since six months ago.”

“So, what happened after you questioned him” – I asked.

“Well, after that we shoot him and then we took his powers away. Nino was a dangerous man, a very powerful person”.

“And what about his wife?”

“She doesn’t have anything to do with that, so we didn’t have any reason to kill her. She was crying and she urinated in her own clothes, so after shooting Nino we took her out of the kitchen. We respect Nino’s wife. She’s a good woman.”

The whole tale was surrealistic and I didn’t quite understand what “taking his powers away” meant.

“Nino had some special powers…”, explains Paul, reflecting a strongly held local belief about the long-time ruler. “…We needed to make sure he won’t come back for revenge. So we hacked his body, with a machete; the hands, the arms, the legs, his belly and his head. Now he’s really dead”. Paul erupts in a smoky laugh, followed by his men.

I give a quick look to the soldiers’ uniforms, and I see that three of them have blood on their boots and pants. I keep on playing the part, and tell them I understand what they did. Then I ask for permission to make portraits of them, with my camera. After I took the picture, Paul led me into an abandoned corner of a warehouse, within the military compound.

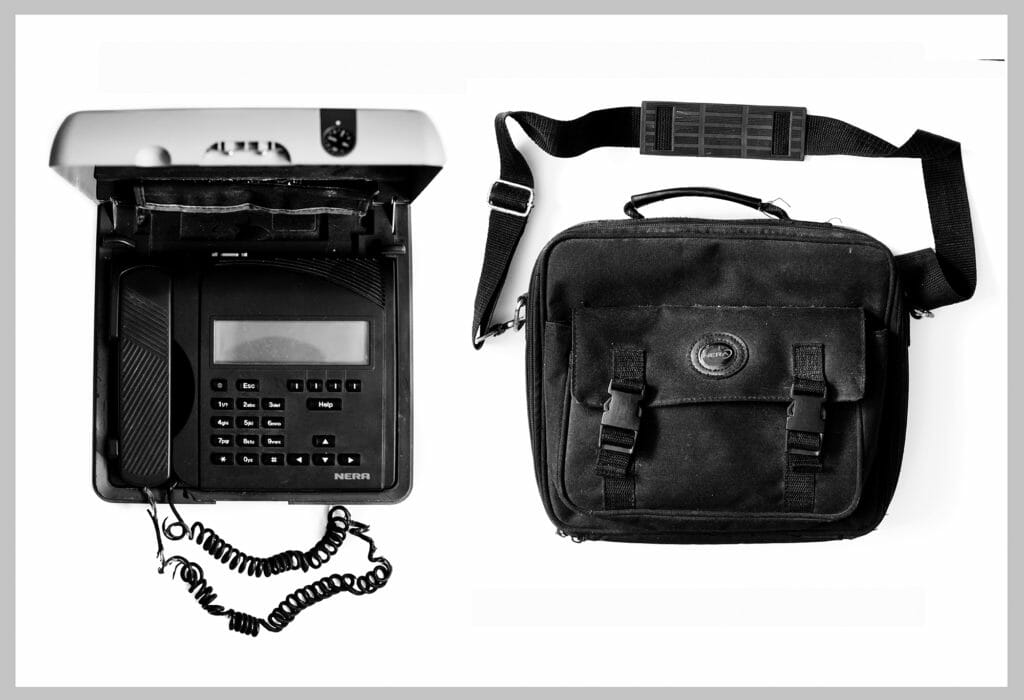

“I have something you could buy, do you want to see?” He called one of his men who came with a black bag. “How much would you pay for that?” – he asked me, his eyes wide-open, as he showed me the president’s satellite phone, stolen from his house few hours before.

“Why should I buy a used satellite phone?,” I said, trying to show as little interest as possible. “I don’t know… what’s your price?”

It was clear that Paul didn’t have a clue. “…Nine thousand Euros, and it’s yours.” I laughed, and said I couldn’t afford that price. So I offered him one more cigarette, and I left.

I spent the next two hours thinking about all the information that was possibly stored in this device. The phone numbers and evidence that would possibly connect Guinea Bissau’s former president with some drug cartels in other countries.

I absolutely needed this phone, but didn’t want to show my interest. I went back to the military headquarters, with an excuse, when Paul spontaneously approached me again. He offered me the phone, once again, and told me I could make the price. I offered 300 Euros. I bought it for 600.

The next day, I managed to visit the president’s house with my camera. One of his several cousins gives me a tour. He led me to the kitchen first, to show me where Nino Vieira was executed. The blood was all over the room. The machete was still on the floor and the bulletproof vest he always wore was on the chair where his wife sat during the questioning. All around there were hundreds of bullets from AK-47 and machine guns. The soldiers looted and destroyed the house. They took everything they could, including clothes and food.

Nino Vieira’s and Tagme Na Wai’s brutal assassinations reflects much more than a mere confrontation between the Papel, the ethnic group to which the President belonged, and the Balanta, Tagme’s ethnic group. It certainly goes beyond the personal settling of accounts.

The spiral of violence began in November 2008, when the head of the navy, Rear Admiral Americo Bubo Na Tchuto, suddenly left Bissau, after the president accused him of plotting a coup d’etat. A month later, in December, the international press reported what appeared to be a “failed attempt at a coup d’etat”, made by 12 soldiers who attacked the presidential compound. But this failed coup was actually about something more.

According to Calvario Ahukharie, the incorruptible national director of Interpol and a crime expert, this escalation of violence is just one piece of a war to gain more control, and personal benefits, over drug trafficking. “The Army, the Navy and the President are all involved – Nino was number one and Tagme number two, and they were competing,” he told me. “Someone had to fall.”