Narco State

A Gangster's Paradise

In Bissau I met a former journalist who had been a correspondent for a Portuguese magazine, I ask him to show me where the local drug lords live. We meet at night, in front of my hotel and we go for a ride through the darkness, where he felt safer than in bar.

“It all started when the fishermen found the drug in the sea…” he tells me while I drive “…a load of cocaine was dumped overboard, from a ship that was intercepted by the Senegalese coast guard, in 2005. The fishermen in Biombo found these packs and didn’t even know what it was. Some of them used it to fertilize their crops, some to paint their bodies and others simply kept the packs in their house. In this country very few knew what cocaine was.” He shakes his head, and smiles bitterly. We pass in front of the UN Building, taking a dark deserted road.

“See this? That’s where Augusto Bliri lives”. My journalist friend points to a huge mansion with a yellow Hummer parked in the courtyard. “That’s the traffickers’ neighborhood. This other house is where Bubo Na Tchuto used to live before he fled to Gambia… I guess the house is empty now… Look, over there, that was Pablo Camacho’s hideout”.

I keep on driving through this kind of Hollywood where the actors are drug lords and show biz is replaced by cocaine trade. Each mansion is guarded by armed security.

Originally Published

Author

Marco Vernaschi

Media

Time, New York Times, Newsweek, Sunday Times, Internazionale, VQR, Global Post, El Pais, BBC, FRIJ, Suddeutsche Zeitung, L'Espresso, Frontline Iwitness CBC

Bliri, Camacho and Na Tchuto. One is the local gangster, one the Colombian trafficker, and one, Na Tchuto, a former Rear Admiral for Guinea Bissau’s navy. Neighbors, and business partners.

Augusto Bliri is a young but talented drug lord who is legend in Bissau. He’s the one who started the cocaine business in the country. He lived in Germany for several years, so when the fishermen found the mysterious packs with the white powder, he instantly knew what to do: he bought some kilos for almost nothing and converted them into hundreds of thousand of Euros.

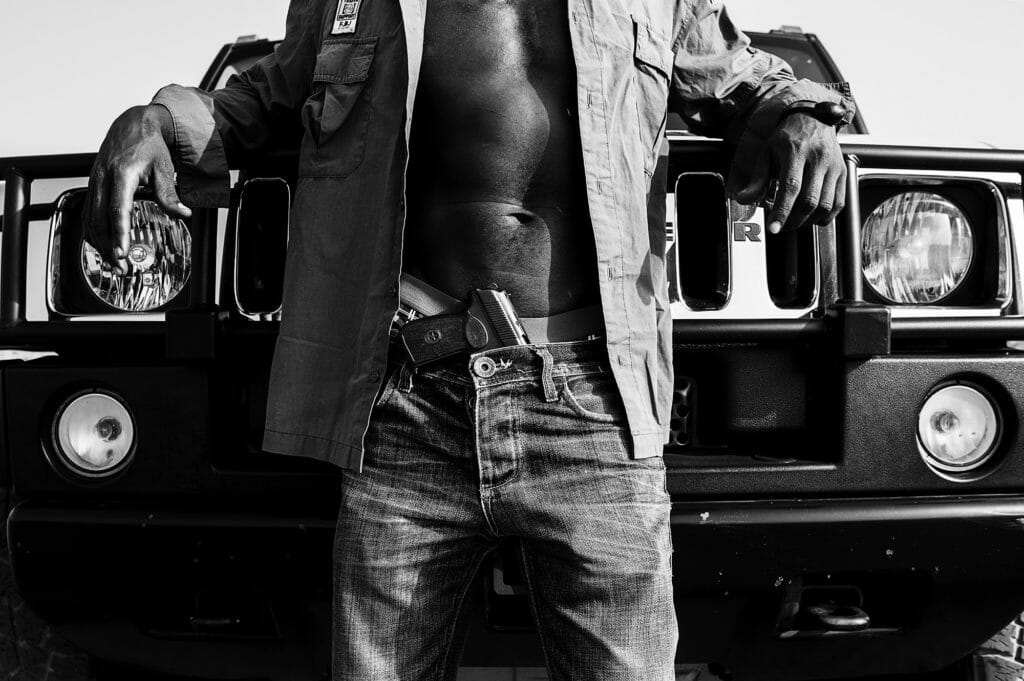

He spends most days driving around in his yellow Hummer and he often visit the Samaritana, a small bar in front of a parking lot in the center of Bissau. In this place, traffickers and dealers share drinks while watching children cleaning their SUVs for few coins. Bliri’s gang is the strongest in town, that everyone either respects or fears, depending on the point of view. A few months ago one of Bliri’s lieutenants killed a Spanish trafficker in Bissau who had tried to steal some cocaine. The police arrested and imprisoned the suspected killer but after three days he was freed. No trial, no evidence. Nothing. The same happened when Bliri was busted and convicted in 2006. The Police found firearms in his Hummer and a large amount of money. He was sentenced to four years but his lawyer, Carlos Lopes Correira, convinced the judge to let him go; his client was sick, Correira argued, and the basement where he was imprisoned was unhealthy.

I ask Lucinda Barbosa, chief of the Bissau police, if Bliri’s gang is in some way connected to the Lebanese network. “Of course they are. The Lebanese are too smart, and would never put their own hands in the fire, so they protect these gangs because they need someone to do ‘the job’. These kids are untouchable, and they know it. They resolve any problem with bribes so they don’t fear anyone.”

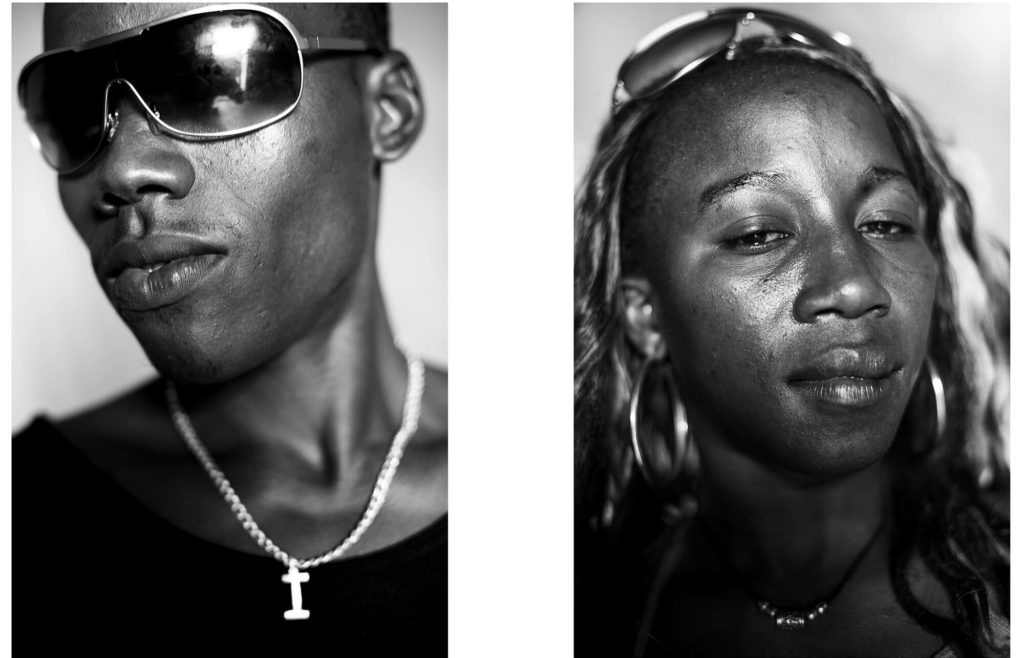

I managed to infiltrate into Bliri’s gang, but in two months I never met him personally. The Interpol knew I wanted to infiltrate, so they provided me with valuable advice and information. I approached one of Biliris’ lieutenants (I will call him Omar, an alias that I promised to use to protect his identity) the third day I was in Bissau. He was smoking marijuana with his friends at the Samaritana. After an improvised conversation about cars and music I suddenly ask him to meet me, this same night.

“I’ll be waiting for you at the Kilimanjaro, at 11 o’clock,” Omar replied. The Kilimanjaro is an isolated, dark patio with a grill that the owner calls “a restaurant.” While approaching the table where Omar was waiting, I realized there was nobody else in this place. Even the owner was gone. But I already was there, with him.

“Have a sit and let’s talk… what can I do for you?” he said shaking my hand. I was a bit nervous, but I sensed he was tense, too. My strategy was to be straight and tell him exactly who I was and what I was looking for.

“I know who you are and what your business is but, frankly, I don’t care. I have no intention to denounce you, nor to give you troubles. I just need you to show me how the whole thing works. I’m a photographer and I’m making a book on cocaine. But don’t worry; nobody will know your name nor see your face. I promise. Would you help me?”

That’s exactly what I told him, word by word. I waited for few seconds, until he replied.

“Holy crap… I don’t know if you’re crazy or brave, but what you are asking for is really risky. I have great respect for you, brother, but you’re a little mad! Do you know you could have been killed if you would have met someone else rather than me?” His answer kind of surprised me, but reading between the lines I understood this was a skeptical “yes”. After the conversation we had a drink. He took my phone number, and then we both left.

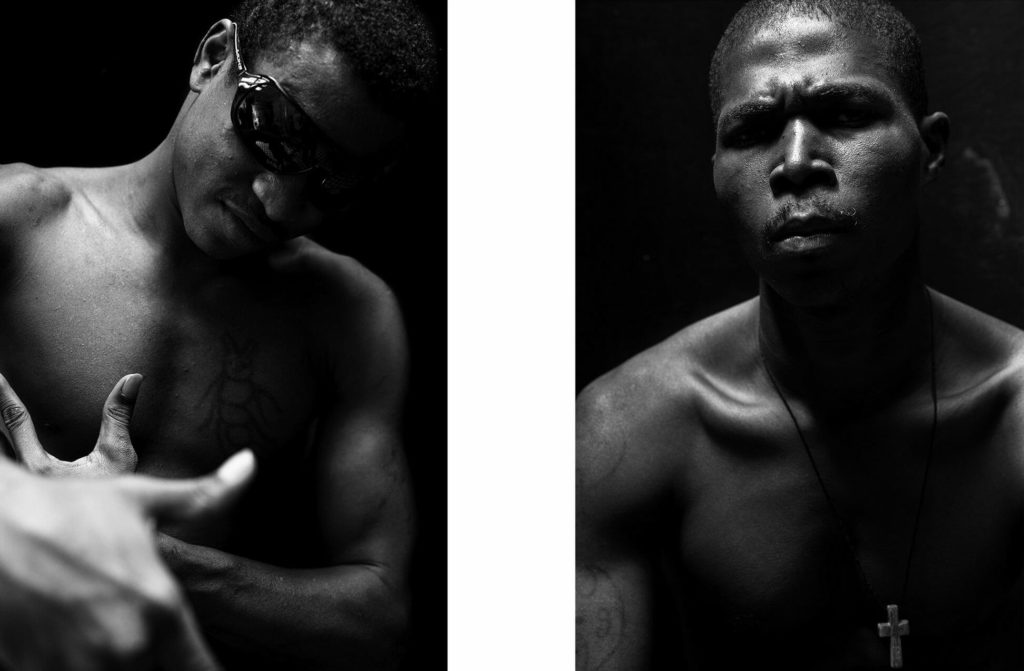

In the weeks that followed I met him almost every day. He tested me several times, gradually opening up to reveal his world. He introduced me to his people, inviting me three times in one week to share dinner with his gang. I’m still not sure if this was a way to have his friends pass judgment on me or if it was, in some way, a spontaneous and sincere attempt at socializing.

In any case I was gaining credibility and Omar’s respect, and after two weeks I felt we really trusted each other. It was carnival in Bissau, and I was invited for a beer at the cabañas of barrio Bra, a place where no stranger would go alone. Everyone was drinking and dancing to the loud beats of Bissau’s pop music. Omar was a little high and started to tell me about his problems with his girl. I think we had become, somehow, friends after this night.

The cliché of drug trafficker that we all have in mind is something that we inherited from Miami Vice or similar movies. In Bissau, most of the gangsters are still very naïve as the drug trade’s dynamics are still new to them. They are mostly kids who never had a single chance, most of them have been living in poverty their whole life, and cocaine trafficking is an unexpected, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, the only real chance to achieve something and leave their slums. Augusto Bliri is the local hero because he was the first who took this chance. He’s smarter than every other local drug lord in Bissau and he’s extremely dangerous, always carrying a gun on his person and an Uzzi in his Hummer.

After some weeks, I ask Omar if Bilri knows that I exist. I already know the answer, but I need to test Omar. He laughs at the question, “If Augusto wouldn’t know about you, we wouldn’t be here now. I gave him my word that you’re reliable. If you do something wrong I will probably get killed, but in this case I wouldn’t be the only who would die. You know, we have our rules here. This is Africa, brother”.

One of the things I liked most about Omar was that he was honest, direct and clear. And he was always on time, a rare quality in Bissau.

We gather for another party in an apparently abandoned lot where the gang set up a wall screen with a DVD projector playing one of 50Cent’s concerts. The grills are crowded with dozens of camaraos tigre, a jumbo shrimp the size of a lobster. Four buckets are filled with beers and a group of girls, the gang’s groupies, dance and shake just like Beyonce taught. The men keep on drinking.

None of them speaks English, but to celebrate they salute 50Cents with a loud “Go, mother fucker!” followed by a big laugh. I’m pretty sure they have no idea what it means, but it’s what the singer says.

“One of these days I’ll show you what happens to those who break the rules” says Omar, holding my arm. He had a strange smile on his face and his eyes were shining when he pointed at mine. I was shivering and asked what he meant to say.

“Ah-ah-ah!” He erupted into a loud laugh “You don’t have to worry, nothing is going happened to you… unless you break some rule…” He keeps laughing, my face paralyzed and my eyes clearly betraying my emotions. “No one is going to die, don’t worry… we don’t kill people that often here… we’re cool. I’m just going to show you something, but not tonight.”

Omar is a good guy, but sometimes he’s a little scary. When I leave the party I keep wondering what he was talking about; but it was a few days later before I had an answer. I was in my room, ready to sleep, when my phone rings, a few minutes before midnight.

“Marco! You should come now. There’s something I promised to show you… remember? Go to the airport, in the parking lot.You will find my friends there in half an hour… and don’t forget your camera!”

I don’t know what to do, I’m freaking scared and I don’t know what I’m about to see. I’m not sure accepting the invitation is wise but it could be maybe dangerous not to. A waltz of doubts and theories starts to dance in my mind, but after half an hour I’m at the airport.

When I arrive, nobody is there. I lock my car, wait for a few minutes, and then a four-wheel-drive arrives. They approach my car and, from the window, a guy tells me to jump on the front seat. Omar is not in the car but I recognize the guy who drives. I don’t know his name and I never talked with him before, but he’s always around at the parties. When I get in the car I see there are three other guys in the back seat. The one in the middle is blindfolded with the two guys at his sides holding a rifle each. One of them wears a SWAT hood, holding a pistol against the hostage.

That’s way too much for me; I want to leave. But I can’t. I wish I was in a movie and I feel ridiculous with my cameras. We drive toward Quinhamel, a little village 30 minutes from Bissau, when the car suddenly takes a secondary road, surrounded by cashew trees. Nobody in the car say a single word. I smoke two cigarettes. In a few minutes the car finally stops. The three guys get off, with their hostage.

“If you want to take pictures, do it. Just make sure not to take my face… I’ll check your camera later”. The driver seemed to be extremely relaxed.

I’m praying they won’t kill him, and I stay in the car. I nervously start to photograph, through the windshield, while outside the gangsters point their rifles at the hostage. They speak Creole, so I don’t understand a single word, but it was clear they were threatening this poor guy with death, asking questions that he never answered. He was so scared he didn’t even cry.

While two of the guys were questioning the hostage, the driver disappeared under a tree. He was comfortably smoking a cigarette.

I get out of the car, with caution. I shoot two or three pictures before they force the hostage on his knee. They point a gun to his head and after more threats they kick him to the ground. The man is shaking. The driver suddenly says we must go, so we get into the car. The hostage is left in the middle of nowhere, at 2 in the morning and far from Bissau. But at least he’s alive.

“You knew we wouldn’t have killed him, right? This guy talked too much … he should pay more attention. The next time he could have serious troubles…”

I still don’t know why Omar allowed me to photograph this. He probably wanted to send me a message, or perhaps just show his power. It’s hard to say, but I’m from another world and like Omar told me once, this is Africa.